Eye For Film >> Movies >> Merchant Ivory (2023) Film Review

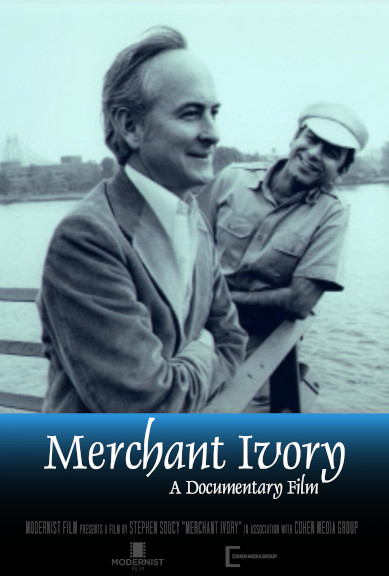

Merchant Ivory

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Speak of Merchant Ivory and most people’s thoughts go straight to English stately homes, elegant costumes and stilted drawing room conversations. This is, however, reflective of only a tiny part of the studio’s output, and even then, the storylines are far from what is popularly assumed. Frequently critical of the aristocracy, if not outright satirical, it also did groundbreaking work around gender and sexuality, and challenged establishment narratives around colonialism. Stephen Soucy’s documentary traces its history across four decades as well as looking back at how its two creative spirits came to meet and moving further on to reflect on Ivory’s work since his partner’s death.

In doing so, it incorporates contributions from some of the most esteemed names in British cinema: Simon Callow, Vanessa Redgrave, Madhur Jaffrey, Emma Thompson – as well as popular stars like Hugh Grant and Helena Bonham-Carter. The voices of studio regulars who are no longer with us are supplied by way of archive footage, and although this bulks the film out to almost two hours in length, nothing feels extraneous. Merchant Ivory made 44 films in total, and Soucy address all the important ones – the formative ones, the unusual ones, those which signalled changes or direction or resulted in altered contracts and funding plans, and of course the hits. What many film fans will not have realised, looking at the sumptuousness of the finished products, is what a shoestring operation it was. Interviewee after interviewee recalls the appeal of great scripts, lovely people, and working alongside other great talents – but also the worry over whether or not they were going to get paid.

They were “fascinating pirates,” says Sam Waterston: Ivory with his gift for casting and for making actors comfortable enough to produce their best work; Merchant who could charm money out of virtually anyone and who kept people loyal with his amazing culinary skills. The two kept their romantic relationship secret for a long time – it was illegal, of course, for the first few years, and would not have gone down well with Merchant’s traditionalist family, but in the circles in which they worked, everybody knew. Ivory speaks briefly about it here, but still finds it hard to relate to the modern idea of coming out. For him it was something very personal and really none of anyone else’s business, although it was at times the cause of quite a bit of drama on set, especially when additional romantic entanglements involved members of the crew. For Soucy, it’s interesting because of the way that it informed and shaped their work.

It began in India, of course, with a mutual love of the work of Satyajit Ray and a series of dates at the cinema. Once they embarked on their own productions, several regular collaborators of Ray’s came on board. There has been plenty of analysis of Merchant Ivory’s English hits, but the analysis of these early films is fascinating and does a lot to inform one’s understanding of their subsequent working model. Like many people working in the creative sector, they found themselves caught between the need to keep trying new things, in order to develop artistically, and the need to build a brand focused on doing one thing well, in order to make money; but unlike most, they persistently opted for the former. Their rewards came in the form of awards, which helped them to access people and resources they wouldn’t have had a hope of getting otherwise; but as Soucy illustrates with one example after another, it was always a frantic balancing act.

Whether you’re a fan of the company’s work specifically or simply interested in the history of cinema, this portrait of its longest-lasting partnership will delight and entertain you. It’s wonderfully detailed and, of course, full of stunning imagery. See it on a big screen if you can.

Reviewed on: 03 Dec 2024